28 November 2025

Tove Jansson and Astrid Lindgren’s shared legacy

What would your childhood look like without the Moomins or Pippi Longstocking? A little greyer perhaps, and far less adventurous. Two Nordic literary icons, Tove Jansson and Astrid Lindgren, created entire worlds that shaped how generations of readers understand family, freedom, and fun – both in the same year.

This article was originally published on moomin.com on 14.11.2025.

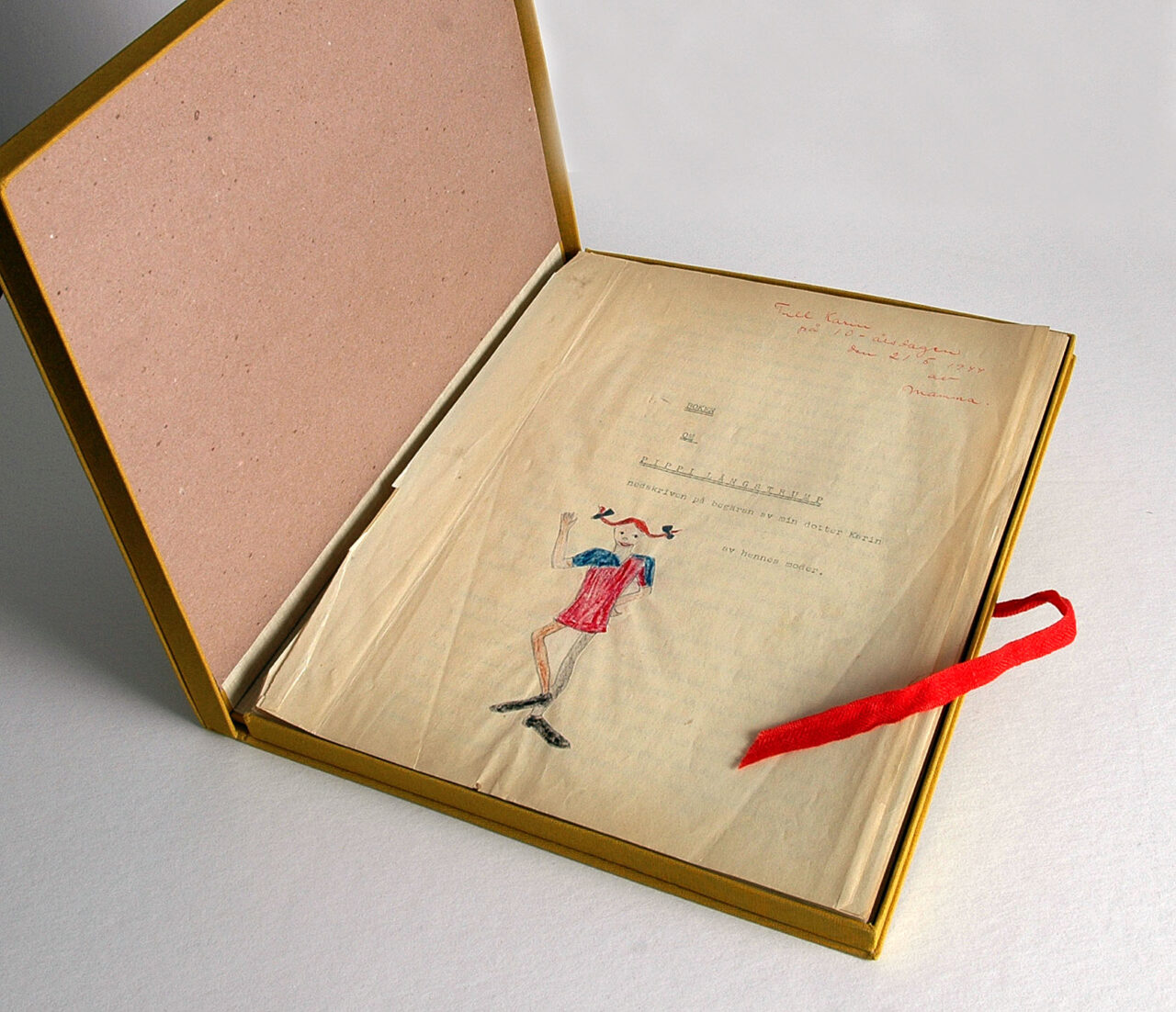

Tove Jansson and Astrid Lindgren were two very different creators. Tove was an artist who told stories with a paintbrush long before she told them with words. Astrid was a publisher, an editor, and a writer who began inventing stories to amuse her own daughter.

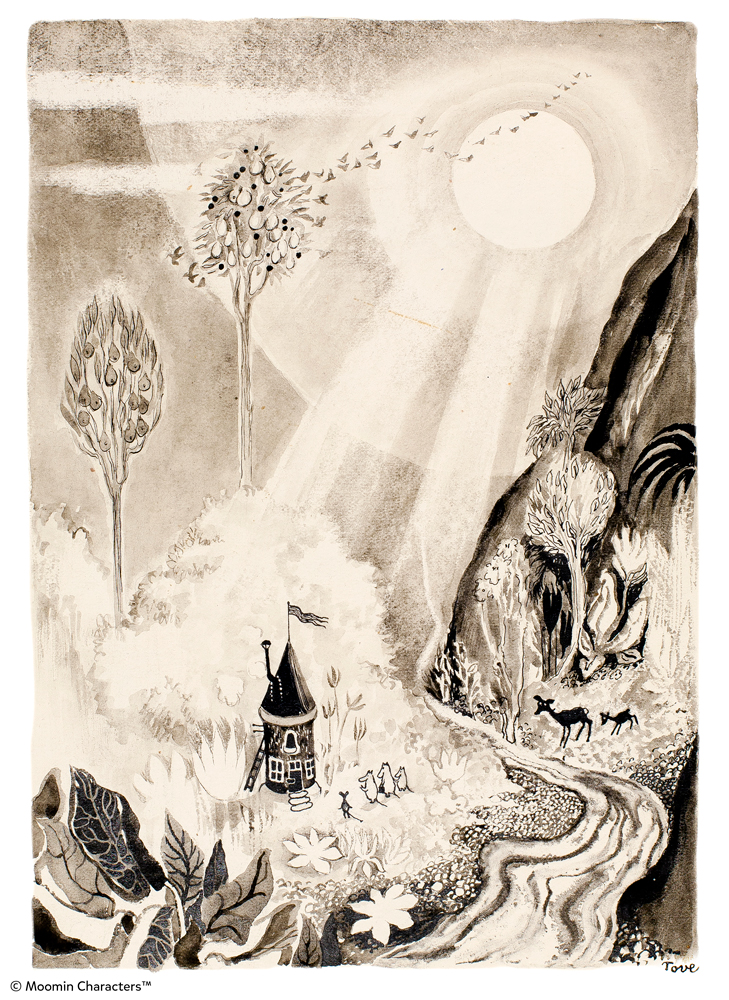

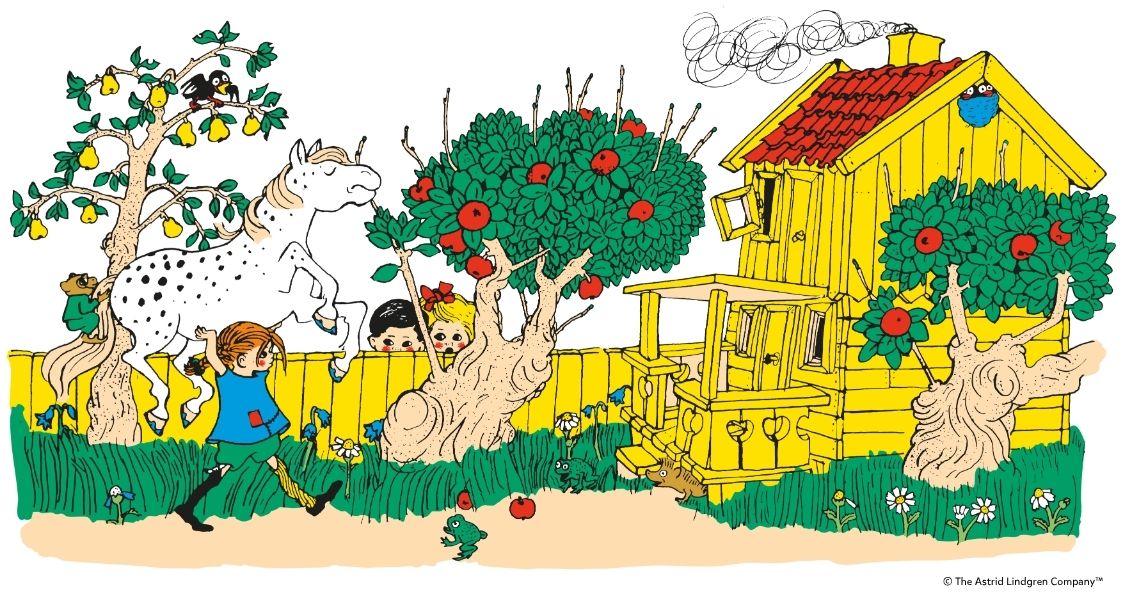

And yet, their work overlapped in unexpected ways. From the round Moominhouse tucked in a lush valley to the crooked Villa Villekulla in a small village, Tove and Astrid gave children new homes to move into: homes built not of bricks and mortar but of play, imagination, and a touch of rebellion.

1945: The year Nordic children’s literature changed

The year 1945 was more than the end of a devastating war. It was a turning point for everyday life. Themes of loss and survival turned into renewal, reflection, and pleasure.

Across Europe, society was slowly reinventing itself. The new times gave women more possibilities as creators, and as mothers, educators, and readers. The artistic society was becoming more organised, and there was a thirst for literature and art that expressed personal experience.

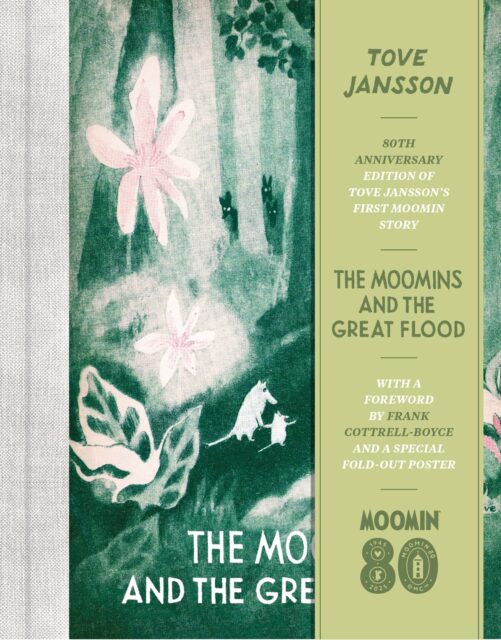

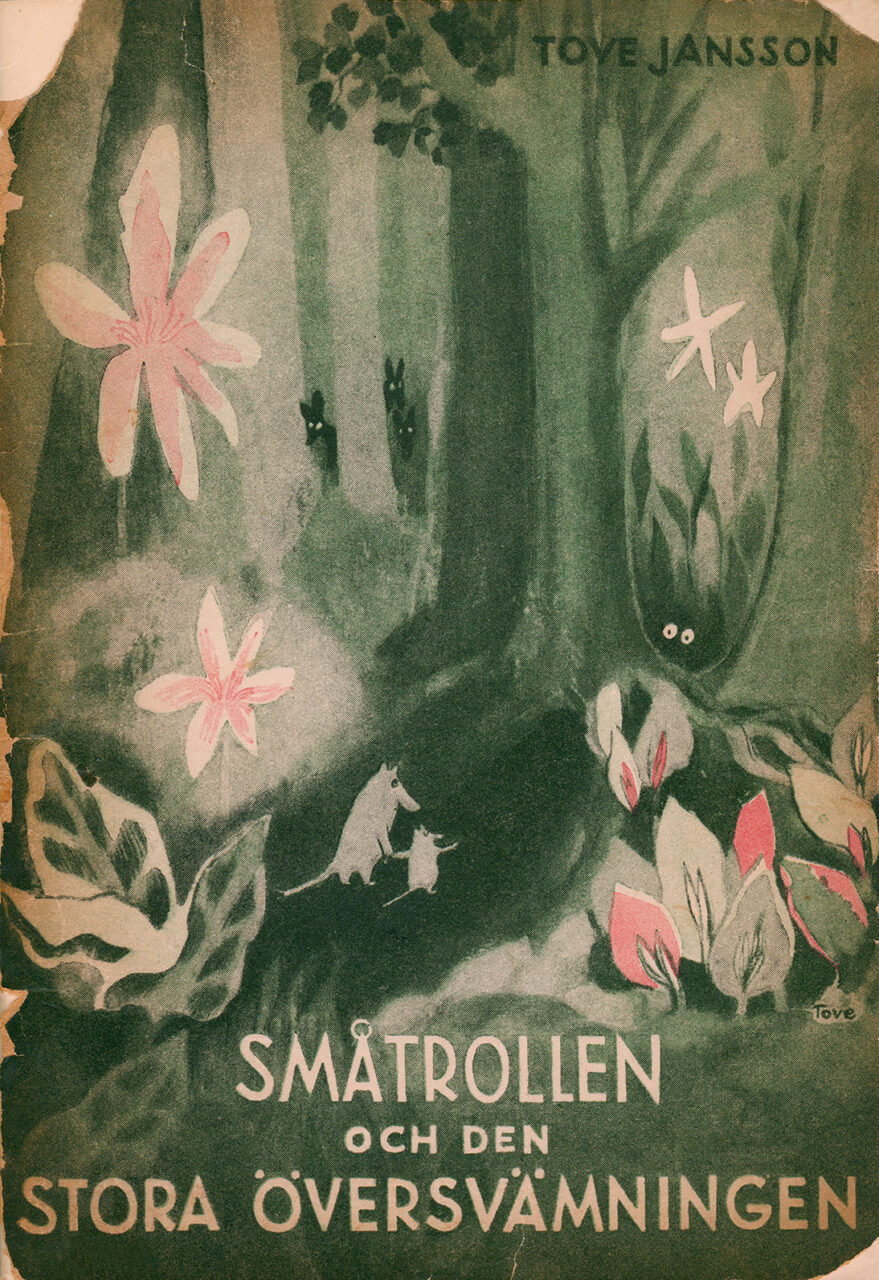

In the Nordics, it was the early days of the welfare state: the beginnings of free daycare and a growing sense that children were central to the future. Into this moment, two very different children’s books emerged: The Moomins and the Great Flood and Pippi Longstocking.

Two different houses became part of the imagination of many children in the Nordics: the round, blue Moominhouse standing as a welcoming beacon for wanderers in search of belonging, and Villa Villekulla, a wonky house of a fearless girl with a horse and a monkey for company.

Both homes broke the nuclear family ideal of the time. Together, they marked the beginning of a new era in Nordic children’s literature; followed by eleven more Moomin books and a whole universe of Astrid’s children’s stories.

Shared legacies beyond the books

Although Tove and Astrid were not personally close, they both helped tilt Nordic children’s literature away from tidy morals and traditional families. On parallel but different paths, they influenced the literary field of the time without influencing each other directly.

Tove Jansson in her Hans Christian Andersen Award acceptance speech in 1966“The job of the children’s author is to give half-articulated, allusive outlines to danger, and the child will colour it in. But the author owes a particular debt to the reader: a happy ending, that is, a happy ending in some way or another.”

Family on your own terms

Tove and Astrid didn’t just write stories; they rewrote what family looks like.

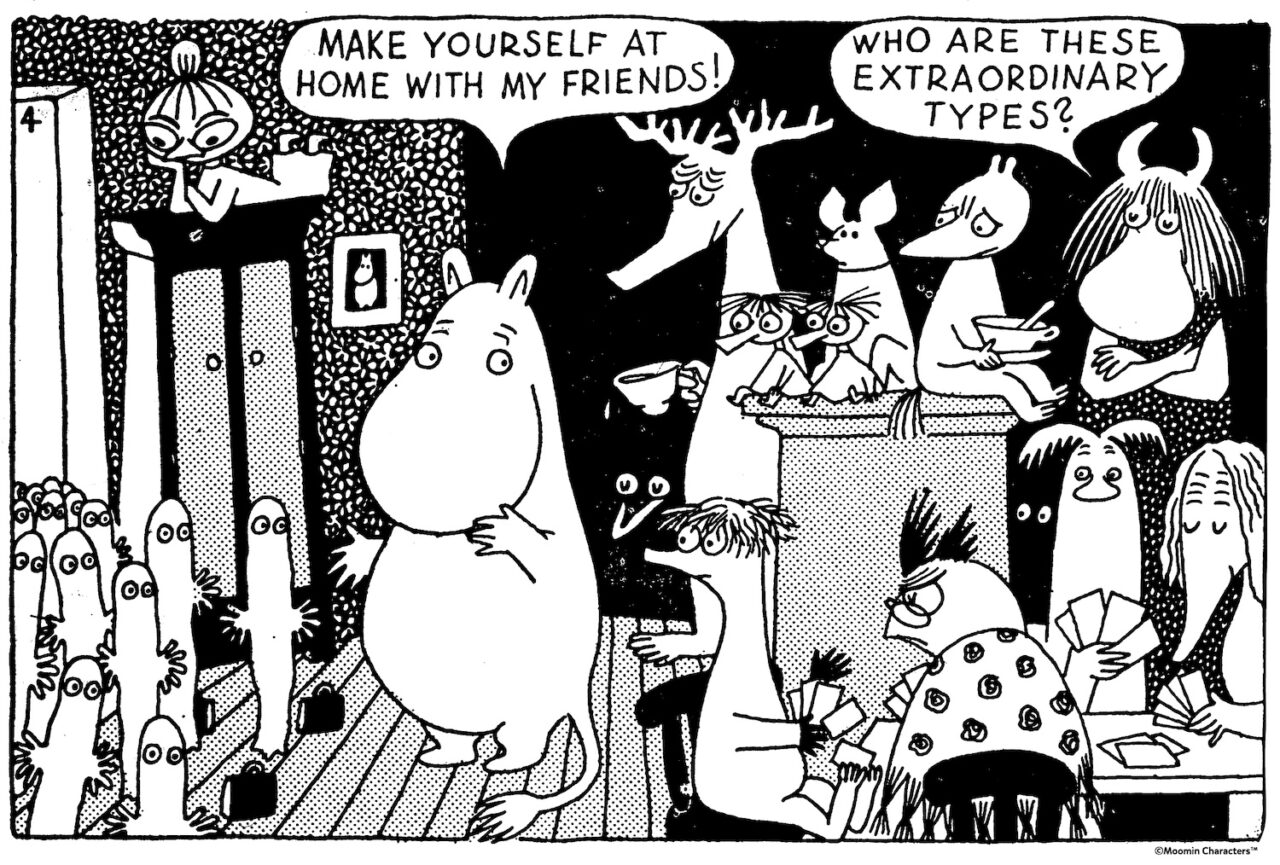

In The Moomins and the Great Flood, it’s Moominmamma and Moomintroll who set out on a journey to rescue Moominpappa: a reversal of the traditional dynamic of the father being the rescuer. Along the way, they meet new friends and strangers who become kin, proving that family is as much chosen as it is given. The door to the Moominhouse is always open, and every guest – whether they stay awhile or forever – is free to be themselves.

Astrid, meanwhile, gave Pippi Longstocking no family at all. Instead, Pippi builds her own “childhome” (as she calls Villa Villekulla) and has a horse, a monkey, and two friends from next door as company. Her mother has passed away and her father is lost at sea, but it’s okay – Pippi is her own parent, cook, and protector (though her pancake breakfasts sometimes defy the laws of kitchen hygiene!). Her household is a declaration that children, too, can create stability, joy, and belonging on their own terms.

Across her other stories too – from the mischievous Emil in Lönneberga to the wild-hearted Ronja the Robber’s Daughter – Astrid Lindgren kept returning to the theme of children carving out their own place in the world.

Both authors invited readers to imagine family not as a rigid structure but as a flexible, expanding circle of love, dissolving boundaries between gender and identity.

From controversy to classics

Another point of connection between Pippi and the Moomins is their desire to push against authority figures. Pippi challenges every adult who tries to tell her how she should behave – policemen, teachers, even burglars are reduced to powerless side characters in her world. The Moomins too, perhaps more subtly, insist that life is too precious to be ruled by rules: in Moominvalley, everyone can live as they wish. Characters like Snufkin and Little My are seen as anarchist advocates for an unapologetic way of life.

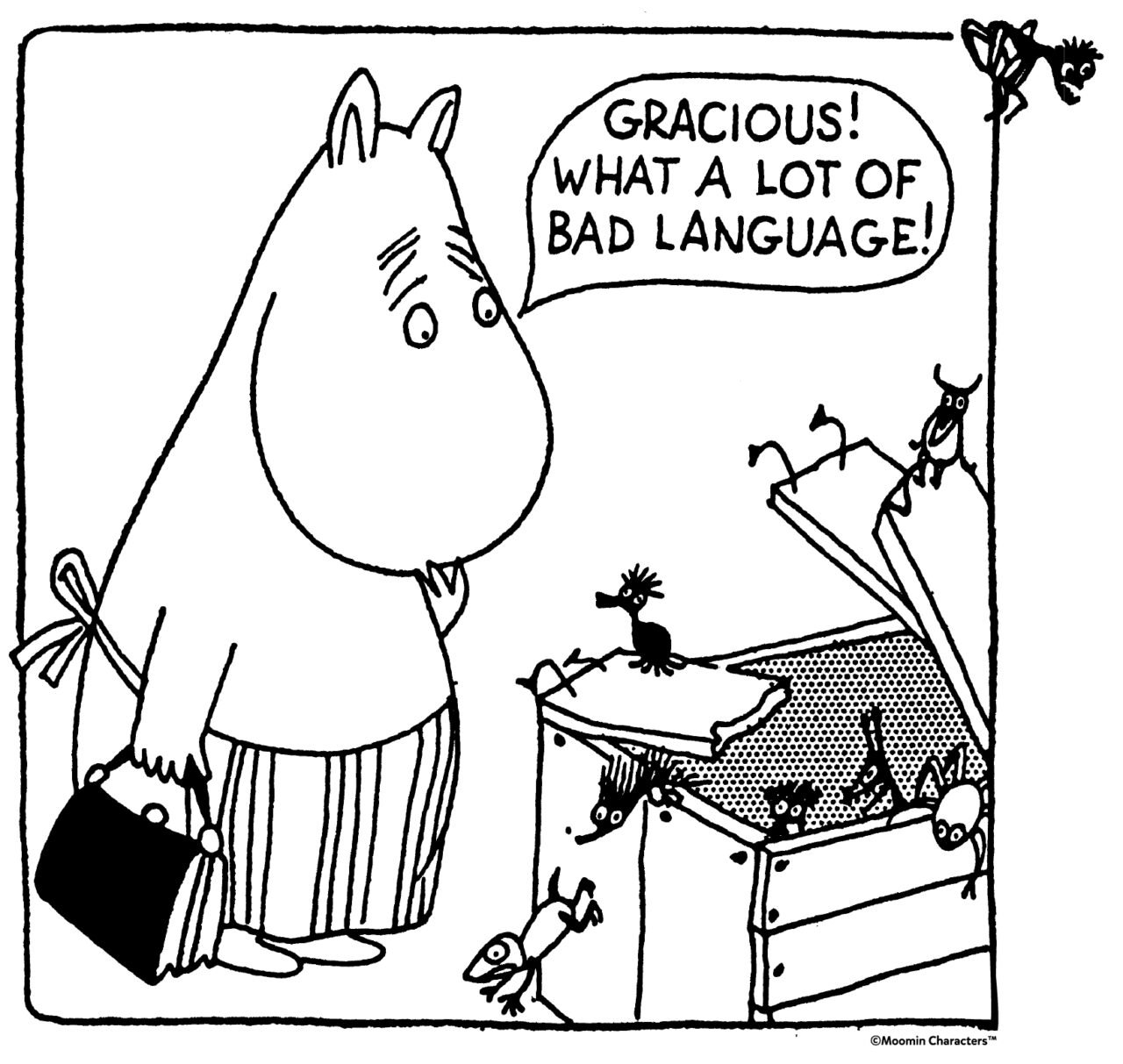

But the world’s reception of these iconic Nordic children’s books at the time was not all roses. Pippi was scandalous to some: too unruly, too independent. Meanwhile, the Moomins were seen as “too dark”, with critics raising eyebrows at the melancholic undertones and a potential bad influence on children, given the Moomin family’s drinking and swearing.

Ironically, both works are now treasured precisely for their boldness. Time, it turns out, has sided with the misfits.

War and wonder

Despite sailing in the same literary waters, Tove Jansson and Astrid Lindgren travelled on very different boats.

The difference lay in the shadows. In Finland, scarred by two recent wars, Tove Jansson was writing in the aftermath of bombings and loss, her first books haunted by floods, comets, and the search for home. In Sweden, which had remained neutral during the Second World War, Astrid Lindgren created Pippi’s anarchic joy: a child who laughed in the face of adversity.

The looming darkness of the Moomin stories wasn’t as relatable in Sweden, as it was in Finland at the time. The reality of war was not present in Astrid Lindgren’s books in the same way as in Tove Jansson’s.

The Moomin stories also differed from many traditional Anglo-Saxian children’s stories in that children don’t need to escape home, or be orphans, to have adventures and find themselves.

Two Nordic literary giants in Middle Earth

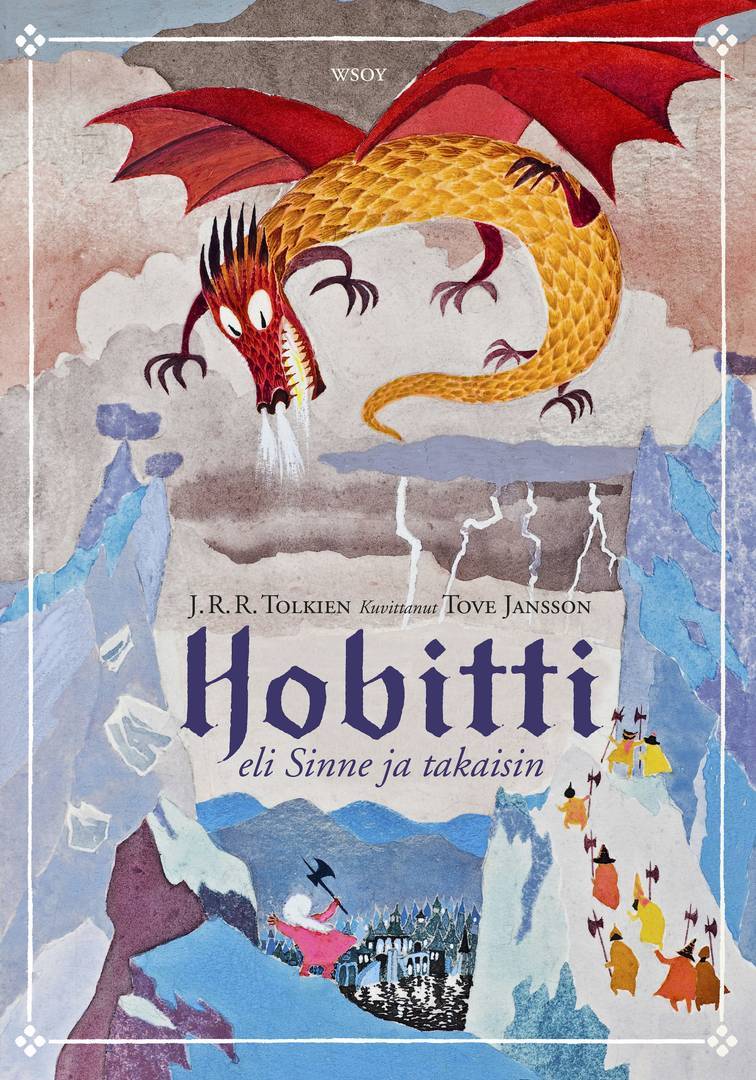

The most significant moment where Tove and Astrid’s careers intertwined was the making of the Swedish translation of J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Hobbit.

One day in 1960, Tove received a letter from Astrid:

“God bless you for Toffle! But who will comfort Astrid if you don’t agree to the proposal I’m now going to make to you?”

(From Boel Westin’s book Tove Jansson: Life, Art, Words)

The proposal was irresistible. The Swedish publisher Rabén & Sjögren was planning a new local translation of The Hobbit, and Astrid, who worked there as a publisher and editor (while also writing her own books) insisted there was only one artist in the world who could visually capture its spirit: Tove Jansson.

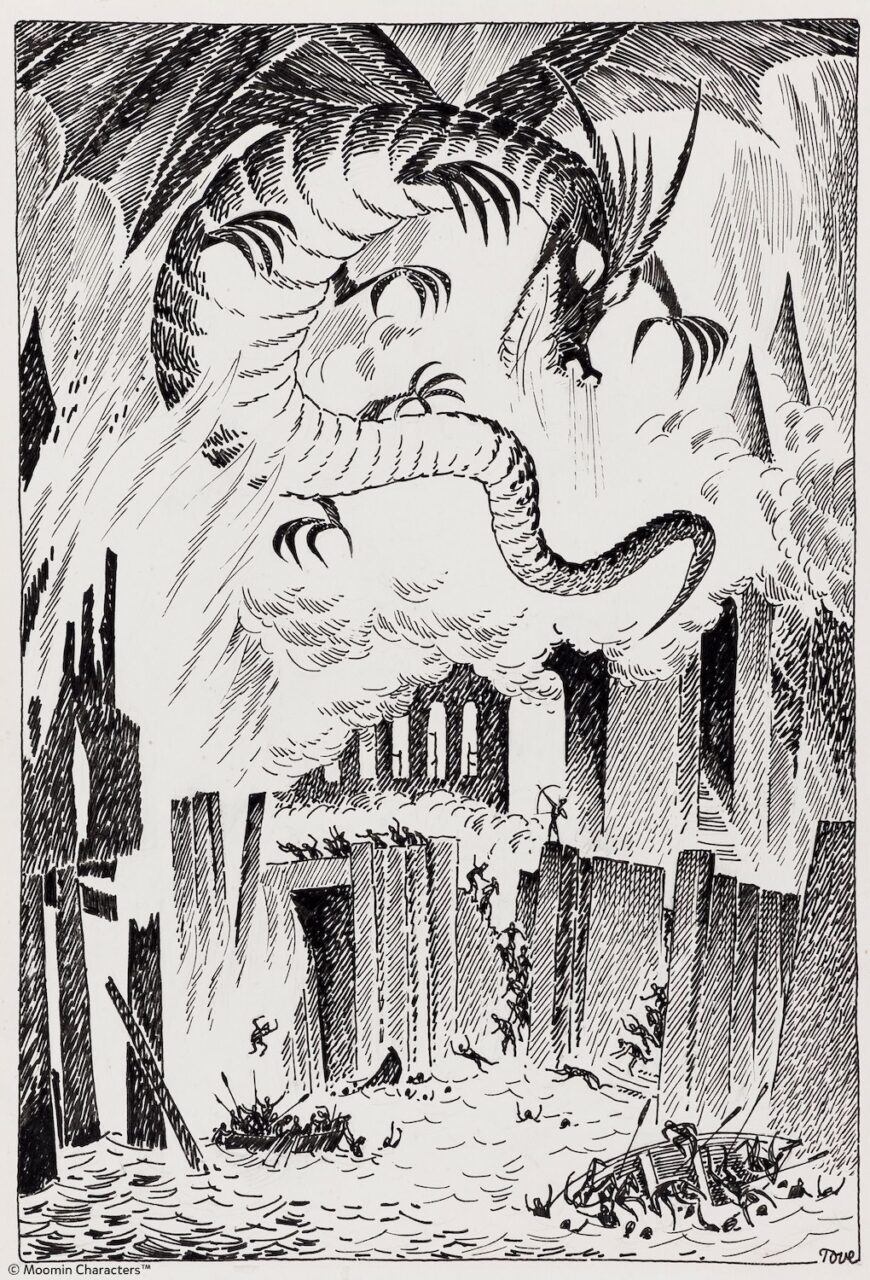

Within a week, Tove had said yes. She was focused on her own painting at the time, but the horror of Tolkien’s world intrigued her. She craved something different from the Moomins.

Astrid was ecstatic. In 1961 she wrote again:

“Dear marvellous Tove, send me the hem of your cloak so I can kiss it! I’m so happy with your wonderful little Hobbit that I can’t find words to say what I feel.”

(From Boel Westin’s book Tove Jansson: Life, Art, Words)

The first Swedish edition, Bilbo – en hobbits äventyr, was published in 1962, and the second in 1994. Tove’s illustrations were also in the Finnish editions from 1973, 2003 and 2011.

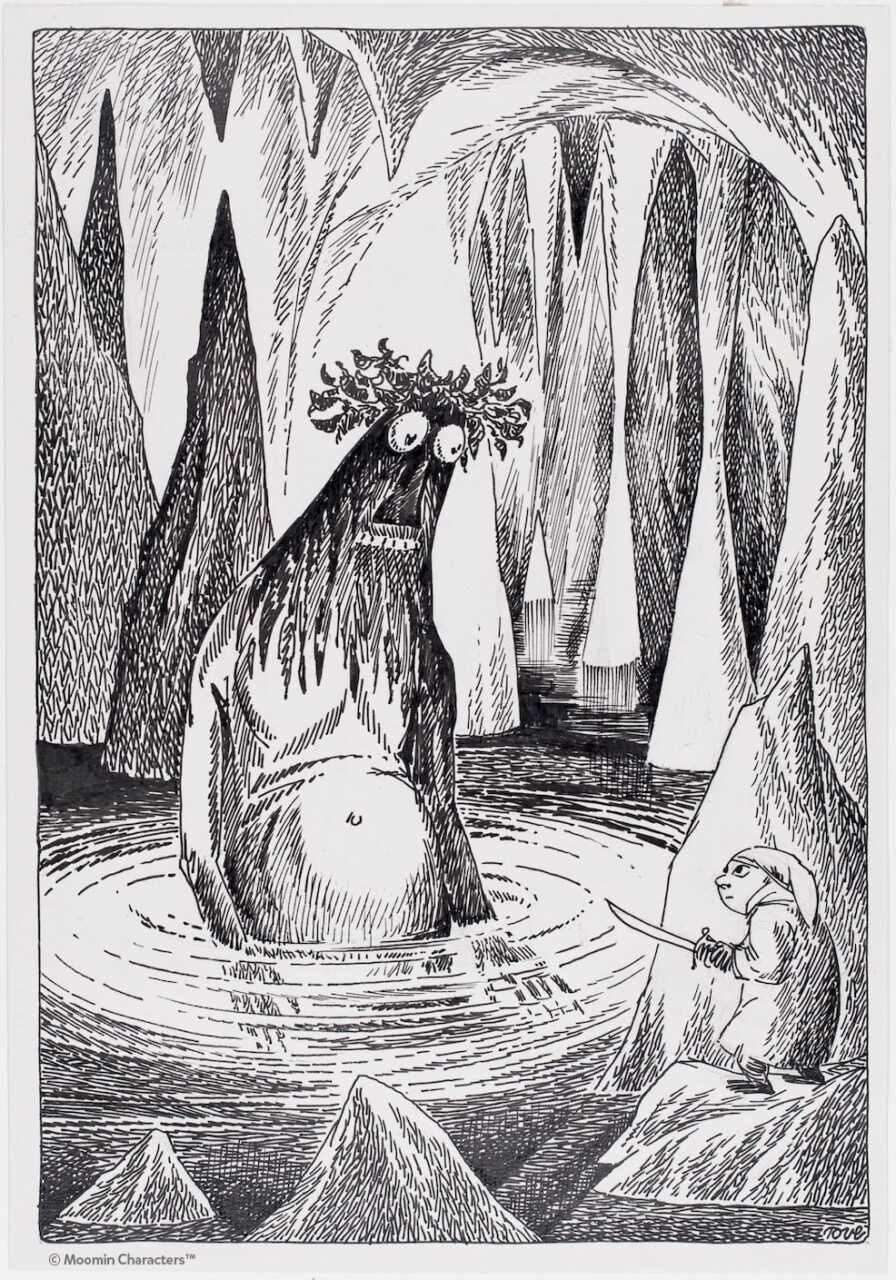

Similar to Pippi and the Moomins, the initial reception was anything but positive. Tove was more interested in the landscapes of the story than the characters, and thus, interpreted the stories in her own way.

Contrary to the interpretation of many fans and Tolkien himself, Tove’s Gollum was gigantic. Tolkien was so taken aback by Tove’s illustration that he added a more detailed description of Gollum into his books, to make sure there wouldn’t be any more misunderstandings about what size he had intended the creature to be.

Despite the public’s first reaction (and the obvious language barrier!), the Finnish edition of The Hobbit is now a popular collector’s item among Tolkien fans in the UK.

This project was the closest Tove Jansson and Astrid Lindgren ever came to true collaboration: two Nordic literary giants shaping Middle Earth, neither as the author but both leaving their marks.

Meeting in ink

Tove Jansson and Astrid Lindgren’s careers overlapped for many years. They met at literary events in Stockholm and Helsinki, exchanged occasional letters about projects, and admired one another’s work. But their personal lives were separate.

Alongside her own writing, Astrid worked as an editor and publisher at Rabén & Sjögren, pairing authors with illustrators and guiding the direction of Nordic children’s literature. Tove, in contrast, was both writer and artist: it was her brushstrokes that had made her known in the first place, and her illustrations were often inseparable from her prose.

Tove also had a lifelong allergy to committees and societies. When invited in 1971 to join the Swedish Academy of Nine, an exclusive literary society, she politely declined – even when Astrid, as chair, tried to persuade her. Tove preferred travel, painting, and her own projects to “great honours.” One exception was the Society of Finnish-Swedish Authors, which she joined for four years.

From Moominvalley to Villa Villekulla

Why do the Moomins and Pippi Longstocking still remain current, so long after they were introduced to the world?

Tove Jansson and Astrid Lindgren gave people permission to be themselves. Pippi can lift a horse with one hand and fry pancakes with the other. Moomintroll can bravely explore the world and find new friends along the way. Both worlds show that strength and kindness, courage and chaos, imagination and responsibility all have room at the same table.

Between Tove’s comets and Astrid’s wonder lies a common truth: children do not need to be shielded from the world, they need to be trusted to navigate it.

In 2025, the world celebrates eighty years since the publication of these iconic stories – both meeting needs that are universal and timeless, and as true today as they were 80 years ago.

Interested in a collaboration with Moomin or Pippi?

Get in touch!

Kristin Tjulander

Nordic Commercial Director